Lupus nephritis is a serious complication of the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus. Abbreviated name for the disease SLE. During the course of the disease, certain antibodies begin to appear in the circulatory system that do not accept the protein molecules produced by the body.

As a result, immune defense is disrupted. The whole process is accompanied by the appearance of inflammatory reactions that manifest themselves in different organs. This disease poses a particular danger to the kidneys.

Lupus nephritis

Lupus nephritis is an inflammation of the kidneys that develops against the background of systemic lupus erythematosus, which is an extensive immune-mediated inflammatory lesion of connective tissue structures. This is a kind of immune defect in which there is an active formation of protein autoantibodies that cause inflammatory processes.

Inflammation affects the skin and joint structures, lung and heart, but the most life-threatening are renal and nervous system lesions. According to statistics, lupus nephritis occurs in approximately 50-70% of cases of systemic lupus. Moreover, this disease occurs 9 times more often in women than in men.

Pathogenesis

The morphological picture of the pathology is characterized by diversity. In addition to histological changes, specific symptoms characteristic of lupus nephritis also occur. The mechanisms of pathological development consist in the fact that there is a violation of the recognition of one’s own organic antigens, as a result of which the active production of autoantibodies begins.

In the presence of predisposing factors, immune B cells are activated, causing the formation of antibodies. This leads to the formation of immune complexes that circulate throughout the body and, settling on various organs, damage their tissues.

Hence the symptomatic diversity of systemic lupus, and nephritis is only one of its many concomitant lesions.

Symptoms of systemic lupus erythematosus

We treat the liver

Warehouse relocation to Europe. We sell hepatitis C drugs in Russia at the purchase price - warehouse liquidation Go to website

The diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has become increasingly common in nephrology hospitals in recent decades. One can judge how relevant the problem of SLE is, at least based on the fact that an article by one of the world’s leading nephrologists, Professor Cameron, “Lupus Nephritis” was published in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology [10:1999] under the heading “Disease of the Month”. And the point is not only that the incidence of SLE has increased, but also the expansion of diagnostic capabilities and, most importantly, a significant improvement in the prognosis of this disease with the use of modern methods of therapy. It is the latter circumstance that requires a doctor of any specialty to be able to promptly recognize or at least suspect the presence of lupus in a patient. Patients with SLE may be seen or admitted to the hospital with a wide variety of symptoms and preliminary diagnoses, and their future fate depends on how quickly the correct diagnosis is made.

Systemic lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune disease characterized by changes in the cellular and humoral immune response. A fundamental disorder in the immune system in patients with SLE is currently considered to be a genetically determined defect in apoptosis (programmed death) of autoreactive clones of T and B cells. In addition to genetic factors, the level of sex hormones plays an important role in the induction of the disease. The negative effect of estrogens is confirmed by the development of the disease mainly in women of childbearing age, the high frequency of onset and/or exacerbation of the disease after childbirth and abortion, as well as low testosterone levels and elevated estradiol levels in men with SLE. Among exogenous factors, great importance is attached to ultraviolet irradiation, bacterial lipopolysaccharides and various groups of viruses that activate B cells, and the use of certain medications, especially hormonal contraceptives.

The loss of immune tolerance to one's own, primarily nuclear, antigens leads to the production of many complement-fixing autoantibodies to components of the cell nucleus, cytoplasm and membranes, in particular to double-stranded DNA and nucleosomes. Autoantibodies have both a direct damaging effect on various organs and tissues, and an indirect effect through the formation of immune complexes and activation of the complement system. It is also characterized by not only immunocomplex, but also thrombotic vascular damage, the latter due to the presence of antibodies to cardiolipin, as well as the development of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and secondary disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thus, systemic damage has a mixed (cytotoxic, immunocomplex and thrombotic) genesis.

Laboratory tests most often detect antibodies to DNA, native (double-stranded) and denatured (single-stranded), the former are more specific, antinuclear antibodies (antinuclear factor), LE cells, antibodies to cardiolipin, including the false-positive Wasserman reaction, and the so-called “lupus anticoagulant” ", which is actually a procoagulant. The name is associated with the peculiarity of the action of this factor in vitro.

Progressive damage to vital organs - kidneys, central nervous system, heart, lungs, blood system - determines the severity and prognosis of the disease. Other organs, joints, serous membranes, and skin are also affected. A characteristic feature of SLE is the fact that even many years after the onset of the disease, the process remains active.

The diagnosis is established when four or more of the following clinical and serological criteria are present (American Rheumatological Association criteria, 1982):

- butterfly rash on the face;

- erythema;

- photodermatitis;

- mouth ulcers;

- arthritis (two or more joints);

- pleuropericarditis;

- kidney damage (proteinuria > 0.5 g/day, cell casts);

- damage to the central nervous system (convulsions, psychosis);

- hematological disorders (hemolytic anemia, leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia);

- immunological signs (anti-DNA antibodies, false-positive RW, LE cells);

- antinuclear factor.

| Table 1. Extrarenal manifestations of SLE in patients with lupus nephritis (own data 2003). |

The systemic nature of the disease and the involvement of the kidneys in the pathological process precisely during the period of its maximum activity lead to the fact that in most cases in the nephrology clinic one has to deal with a variety of extrarenal manifestations of SLE (see Table 1). These include pulmonary infiltrates and alveolar hemorrhages, cerebrovasculitis and transverse myelopathy, thrombotic lesions of the vessels of the lungs, extremities, intestines, brain, endo-, myo- and pericarditis, lesions of the liver, joints, thrombocytopenia, anemia, lymphadenopathy, serositis, various skin manifestations and other symptoms. Damages of the central nervous system and lungs have the greatest prognostic significance.

Involvement of the central and peripheral nervous system in SLE is quite common - up to 50% of cases. Cerebrovasculitis, movement disorders, mono- and polyneuropathy, aseptic meningitis, acute psychosis, cephalgia, dysphoria, and convulsions are noted. Transverse myelopathy is, although quite rare - 1-3%, but prognostically unfavorable and difficult to treat, a manifestation of the disease.

Lung damage is most often observed in the form of pulmonitis and pulmonary embolism (PE). Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage develops in less than 2% of patients with SLE, the mortality rate for this pathology is 70-90%.

Great importance is currently attached to antiphospholipid syndrome. The APS examines such manifestations of the disease as heart valve lesions, coronary artery thrombosis, thrombotic pulmonary hypertension, purpura and leg ulcers, Evans syndrome (a combination of hemolytic anemia with thrombocytopenia), Sneddon syndrome (arterial hypertension, recurrent thrombosis of the cerebral arteries and marbled skin pattern ).

Among heart lesions, pericarditis is the most common (up to a third of cases), and among patients with the active stage of the disease, the prevalence of pericarditis is even higher - it is observed in more than half of patients. In some of them, pericarditis is the first manifestation of SLE. A serious complication is cardiac tamponade, which, however, occurs quite rarely - approximately 1% of cases.

Lupus glomerulonephritis (LGN) is one of the most serious and prognostically significant manifestations of SLE. The mechanism of development of lupus nephritis is immunocomplex. Binding of anti-DNA antibodies and other autoantibodies to the glomerular basement membrane leads to complement activation and recruitment of inflammatory cells to the glomeruli.

Clinically, renal pathology is detected, according to various authors, in 50-70% of patients, and morphological changes are detected even more often. Studies of renal biopsies from large groups of patients have shown that renal involvement occurs in almost all cases of SLE. Even in the absence of urinary syndrome, it is extremely rare that no changes are detected in the biopsy material, especially when using immunofluorescence and electron microscopy methods. In addition to CAH itself, renal thrombotic microangiopathy, thrombosis of the renal arteries and veins caused by the presence of antiphospholipid autoantibodies, and immunocomplex tubulointerstitial damage can also develop.

The clinical picture of glomerulonephritis (GN) in SLE is diverse (see Table 2) and includes almost all currently identified options: minimal urinary syndrome; severe urinary syndrome in combination with hypertension; nephrotic syndrome (NS), often combined with hematuria and hypertension, and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. At the same time, there are no specific clinical signs that are characteristic specifically of lupus nephritis and allow diagnosing SLE only on the basis of symptoms of kidney damage.

| Table 2. Clinical manifestations of lupus nephritis. |

The dominant symptom is proteinuria - up to 100% of cases; NS develops in approximately half of the patients. Microhematuria is almost always present, but is not isolated; macrohematuria is quite rare. Severe forms of the disease predominate, the prevalence of which reaches 63%. Arterial hypertension was recorded in 50% of cases, more than half of the patients showed a decrease in glomerular filtration rate, and tubular functions were also impaired. Kidney damage often develops at the beginning of the disease, against the background of high activity of the process, sometimes becomes its first manifestation or occurs during an exacerbation.

The morphological changes are also varied. There are signs characteristic of CAH (fibrinoid necrosis of capillary loops, hyaline thrombi, wire loops), which in some cases makes it possible to diagnose SLE based on the results of a kidney biopsy, but changes characteristic of GN as a whole can also be detected. According to the domestic classification of V.V. Serov (1980), focal proliferative lupus nephritis, diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis, membranous GN, mesangioproliferative GN, mesangiocapillary and fibroplastic GN are distinguished. The WHO classification (1995), based on data from light, immunofluorescence and electron microscopy, allows us to distinguish six classes of changes.

When comparing these two classifications (see Table 3), parallels can be noted between mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis and class II and, in part, between focal proliferative lupus nephritis and class III. Class IV includes diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis, as well as cases of mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis. Class V corresponds to membranous nephritis, and VI to fibroplastic.

The frequency of detection of different morphological classes varies, most often - up to 60% of cases - changes in class IV are detected, which, according to most researchers, is considered to be the most unfavorable prognostically. In addition to the morphological type, impaired renal function, arterial hypertension, severe hematuria, as well as male gender, high titers of antibodies to DNA, low levels of complement, anemia, thrombocytopenia and the presence of polyserositis have a negative prognostic value.

The course of the disease and prognosis for SLE in general and for CAH in particular cannot currently be considered independently of the results of treatment. Over the past 40 years, the prognosis of the disease has improved significantly (see Table 4). Five-year actuarial survival almost doubled for both SLE overall and CAH. With RLN with class IV changes, the dynamics are even more pronounced. If 30 or more years ago the survival rate of patients with class IV CAH rarely exceeded one to two years, then subsequently the five-year actuarial survival rate increased more than fourfold.

| Table 4. Dynamics of five-year actuarial survival for SLE, LN and LN with class IV changes over 40 years. JS Cameron—J.Am.Soc.Nephrol, 1999 |

The principles of SLE therapy have undergone significant changes. The administration of small and medium doses of corticosteroids (CS) in intermittent courses has been replaced by regimens that involve long-term administration of high doses of CS in combination with cytostatics (CS): in particular, “pulse therapy” with ultra-high doses of methylprednisolone (MP) and cyclophosphamide ( CF). Plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin G and, more recently, cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil have also been used. At the same time, there remains interest in the use of antimalarial drugs in the benign course of SLE.

The classic version of “pulse therapy” is the intravenous administration of 1000 mg of MP over the next three days, which leads to suppression of the activity of B-lymphocytes and a decrease in the level of immunoglobulins and immune complexes. This method was first used by Kimberly in 1976; it is effective for many extrarenal manifestations of SLE - fever, polyarthritis, polyserositis, cerebropathy, cytopenia. In cases of transverse myelitis, its effectiveness is lower - about 50%. This method is also of great importance in the treatment of lupus nephritis: after carrying out “pulses,” prednisolone (PZ) is prescribed orally at a dose of 60–100 mg per day; in severe forms, repeated MP “pulses” are used at a dose of 1000 mg monthly for 6– 12 months.

In severe forms of SLE, intravenous administration of high doses of CP is widely used. With active lupus nephritis, the best results are achieved by performing “pulses” at a dose of 1000 mg of the drug monthly for six months and then 1000 mg every three months for a long time - up to one and a half years. There is also a more intensive regimen - 500 mg of CP weekly for up to 10 weeks. In patients with simultaneous damage to the kidneys, skin, mucous membranes, central nervous system, cytopenia and high immunological activity, it is advisable to combine high doses of MP and CP. Combined “pulse therapy” is especially relevant for hemorrhagic pneumonia and involvement of the central nervous system in such forms as transverse myelitis and damage to the optic nerve.

The effectiveness of therapy with high doses of CS in combination with CS for CAH, including those with class IV changes, has been shown in many studies and controlled studies. The advantages of therapy with a combination of CP with prednisone, compared with PZ monotherapy in patients with proliferative CAH, are clearly confirmed by renal survival rates.

Ten-year renal survival rate with the combination of PZ and CS reaches 85-90%; the best results were observed with the use of combined “pulses” compared to the use of PZ and CS orally or only PZ. Long-term treatment with CF “pulses” with a transition to quarterly administration for two years has advantages over “pulse therapy”; Only MP can be considered optimal for preventing exacerbations of the disease. A favorable prognosis is associated with a lower creatinine level at the beginning of therapy and its normalization during treatment, with the absence of arterial hypertension and a decrease in proteinuria to 1 g/day or less.

Our clinic has also accumulated some experience in treating patients with SLE. Of 56 patients observed from 1991 to 2002, we analyzed 41 cases of lupus nephritis (including 17 with a morphologically verified diagnosis, nine of them with class IV changes) with various extrarenal manifestations. Moreover, if in the general group of patients various treatment regimens were used (CS only, CS and CS orally, CS and CS both orally and as “pulses”), then in eight patients with class IV changes, “pulse therapy” was used. This is explained by the fact that, due to the nature of the work of a large multidisciplinary emergency hospital, the clinical material is very heterogeneous. The vast majority of patients were initially hospitalized on an emergency basis, with various preliminary diagnoses, often in therapeutic, surgical and urological departments. The severity of the patients' condition, limited laboratory testing capabilities and the shortage of drugs necessary for the use of modern treatment regimens led to the fact that treatment was often carried out empirically. Only in the last few years have we been able to fine-tune the mechanism for providing adequate and timely treatment.

The advantages of “pulse therapy” for the most unfavorable form of VL are clearly reflected in Table 5.

| Table 5. The effectiveness of therapy in patients with SLE with kidney damage and class IV LN (own data, 2003). |

The most common complications of CS therapy are Cushingoid appearance, osteoporosis, gastrointestinal ulcers, cataracts, and diabetes. Side effects of MP “pulse therapy” are manifested by tachycardia or bradycardia, and blood pressure fluctuations. Complications with the use of CF are mainly dysfunction of the gonads and inhibition of hematopoiesis. With intravenous administration of CP, hemorrhagic cystitis is rare and is prevented by adequate hydration. Herpes zoster usually occurs in young patients. With intravenous administration of CP, compared with the use of CS orally, the likelihood of oncogenic effects also decreases, since the threat of tumor development is actually considered with a total dose of CP of more than 60 g. Complications such as thrombosis, malignant neoplasms, infectious complications, including sepsis , progressive atherosclerosis, aseptic bone necrosis, cytopenia, are considered as side effects of SLE itself, possibly increasing with all types of therapy. Overall, complications occur in approximately half of patients. Among the causes of death, the first place is occupied by septic complications, including against the background of SLE resistance to therapy, and coronary heart disease is in second place.

Based on the analysis of literature data and our own observations, it should be noted that the prognosis of ULN, which poses a significant danger to the lives of patients, can be significantly more optimistic when carrying out immunosuppressive treatment, although the latter is a complex and time-consuming task due to the duration of therapy and the presence of side effects and complications. Nevertheless, the use of combined “pulse therapy” of CS and CP seems to be the most effective and safe method for CAH.

As an example of the difficulties of diagnosis, as well as the successful use of “pulse therapy” in SLE with class IV CAH, damage to the skin, joints, serous membranes, liver, and the rather rare Evans syndrome, we will give our own observation. Patient T., 23 years old, a student, developed facial erythema after sun exposure in the summer of 1999, for which in September the plastic surgery clinic treated her with drugs that stimulate collagenogenesis. The erythema persisted, marbling of the skin of the extremities and chest appeared. At the end of December, after an emotional shock, febrile fever and arthralgia occurred, and she took NSAIDs. A week later, swelling of the face, shortness of breath, and an enlarged abdomen were noted. At the beginning of January 2000, she was hospitalized in the department of medicinal pathology, from where, a day later, due to increasing shortness of breath, she was transferred to the City Clinical Hospital named after. S.P. Botkin was admitted to the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of bilateral pneumonia and laryngeal edema.

In the reception department of the City Clinical Hospital named after. S.P. Botkina’s diagnosis of laryngeal edema was not confirmed; she was hospitalized in the therapeutic department in serious condition. Puffiness of the face and butterfly-shaped erythema, a marbled pattern of the skin of the trunk and extremities, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, bilateral hydrothorax were noted, fluid was found in the pericardium, and an increase in LDH levels to three norms was detected. The next day, the patient was consulted by a nephrologist about edema syndrome. SLE was diagnosed, CS and immunological examination were prescribed. Therapy with dexazone 24-36 mg/day intravenously was prescribed, but the patient’s condition continued to deteriorate - shortness of breath increased, intense bursting pain in the abdomen and hypotension appeared. A decrease in the level of hemoglobin from 98 to 60 g/l, platelets from 288 to 188 thousand per μl, reticulocytosis to 18%, a positive Coombs test, an increase in aminotransferases to three to four norms and moderate hyperbilirubinemia in the absence of markers of viral hepatitis were detected. The combination of hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia gave grounds to diagnose Evans syndrome in the patient. At the same time, an increase in proteinuria was noted up to the formation of NS; LE cells were found in the blood, titres of antibodies to DNA increased to six norms, antinuclear factor titre 1/80, antibodies to cardiolipin, cryoglobulins. The dose of CS was increased to 60 mg of prednisolone per day.

The patient was transferred to the nephrology department, where she was started on “pulse therapy” with metipred - daily “pulses” in a total dose of 3000 mg. The patient's condition improved significantly, hypotension was eliminated, temperature normalized, hemoglobin and platelet levels increased, bilirubin and transaminase levels normalized. Therapy with oral prednisolone at a dose of 60 mg/day continued, and the first “pulse” of CF was performed. Skin manifestations and polyserositis gradually regressed, but nephrotic syndrome persisted and hepatomegaly persisted.

A month after admission, a puncture biopsy of the kidney was performed, with a histological examination performed at the Department of Pathological Anatomy of the Moscow Medical Academy named after. I.M. Sechenov, a picture of mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis was obtained. “Pulse therapy” was continued with combined “pulses” and CF monthly, PZ inside. After two months, extrarenal manifestations were completely eliminated; by the end of the fourth month, partial remission of NS was achieved; the oral dose of PZ was gradually reduced to 30 mg/day. By the end of the ninth month of treatment, complete remission of all manifestations of the disease was stated; it was planned to switch to quarterly “pulses” of CF, which was not carried out due to leukopenia and candidiasis of the oral cavity and vagina. “Pulse therapy” was stopped when the total dose reached 8000 mg and CP 6400 mg, the oral dose of PZ was subsequently reduced to a maintenance dose of 7.5 mg/day by May 2001, and remains stable to this day. A cataract was diagnosed that did not require surgical treatment; the manifestations of exogenous hypercortisolism regressed. The patient continues to be observed in the clinic, complete remission of the disease persists for almost three years, the total duration of observation is three years and eight months.

In conclusion, I would like to emphasize once again that the problem of diagnosing and treating SLE is very relevant not only for rheumatology and nephrology, but also for other areas of medicine that at first glance seem distant from it. Patients with SLE are often examined and treated for a long time with various diagnoses on an outpatient basis or hospitalized in infectious, neurological, gynecological, tuberculosis and other hospitals, which is why patients do not receive adequate treatment in a timely manner. Meanwhile, modern immunosuppressive therapy can radically change their fate. In this regard, it is necessary to once again remind doctors of various specialties that systemic lupus erythematosus is not a rare, serious, life-threatening disease that requires timely diagnosis and treatment.

E. V. Zakharova State Clinical Hospital named after. S. P. Botkina, Moscow

Source: www.lvrach.ru

We are in social networks:

Causes

There is no single theory explaining the appearance of systemic lupus erythematosus, so experts identify a group of factors that can lead to this pathology:

- Female hormones of the reproductive system. Estrogens are often trigger factors for the development of systemic lupus. This partly explains the tendency of the female population to this pathology. In addition, systemic lupus often manifests during pregnancy, when estrogen levels are at their maximum.

- Heredity. Experts note a certain pattern in the development of such a disease in people who have relatives with a similar pathology. The incidence is especially high among twins. Also, a tendency to systemic lupus is observed in Afro-Caribbean ethnic groups, where the pathology is detected 10 times more often.

- A history of infectious viral pathologies. Particularly dangerous viruses and most often leading to the development of lupus are retroviruses, paramyxoviruses, measles viruses, etc. However, the viral theory is still being studied and requires additional evidence. Although existing research results allow us to consider it as a significant factor.

- Medications. It has been clinically proven that long-term use of drugs like Methyldopa or Isoniazid can provoke the development of pathology.

- Excessive sun exposure. Excessive ultraviolet radiation has been proven to have a significant influence on the development of systemic lupus.

Video shows the effect of systemic lupus erythematosus on the kidneys:

Symptoms

External signs of lupus nephritis are quite diverse.

The final clinical picture consists of signs characteristic of nephritis and lupus in general:

- Skin lesions. They appear as erythematous (red-colored) butterfly-shaped lesions on the facial skin. There are often rashes in other areas of the body.

- Kidney lesions.

- Hyperthermia, which can reach high levels.

- Vascular lesions, which consist of inflammation of small vascular channels at the fingertips. Less commonly, capillaritis affects the palms and soles.

- Articular lesions that manifest themselves as arthritis of small joint structures.

- Cardiac lesions – myocarditis, pericarditis, endocarditis.

- Pulmonary lesions, which manifest themselves as pleurisy and fibrosing alveolitis.

- Lupus cerebrovasculitis.

- Trophic disorders such as alopecia, rapid weight loss, split nails.

More specific symptoms depend on the type of lupus nephritis.

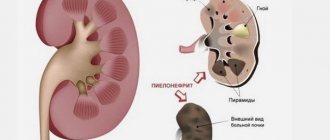

Pathomorphology

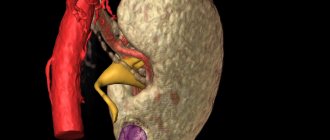

Lupus nephritis has various morphological manifestations. During the autopsy of a sick person, the doctor noted the large presence of ball formations in the kidney tissue. There were traces of active division of cellular structures in the body. Sclerosis of parts of the vascular system is also observed.

The most common phenomenon of lupus nephritis is fibrinoid necrosis of the Henle capillary network. In addition, the presence of changes in the basement membrane is noted in the body. Immune complexes are displayed as the presence of thrombus-like formations in the lumens of the capillary network.

Kinds

Experts identify several types of lupus nephritis. In accordance with the severity of inflammatory changes, lupus nephritis is divided into diffuse and focal, with or without symptoms of glomerulonephritis. In addition, lupus nephritis is divided into the following forms:

- Inactive nephritis – accompanied by subclinical proteinuria and minimally expressed urinary syndrome;

- Active lupus nephritis, which is also classified into several forms:

- Rapidly progressive;

- Slowly progressive (occurs with urinary or nephrotic syndrome).

The rapidly progressive form of lupus nephritis is similar in symptoms to malignant chronic glomerulonephritis. Such nephritis most often causes kidney failure and manifests itself already in the first year of development of systemic lupus.

Clinical manifestations rapidly increase, generally reducing to a pronounced nephrotic syndrome:

- The patient is concerned about severe swelling, up to a massive accumulation of fluid in various cavities, for example, in the heart, peritoneum, pleura, etc., and swelling of the legs is also observed.

- There is severe hypertension, and high blood pressure levels are quite difficult to treat with traditional drug correction.

Slowly progressing lupus nephritis is characterized by a milder and benign course. It accounts for about 40% of all lupus nephritis. If slowly progressing lupus nephritis is accompanied by nephrotic syndrome, then the swelling is mild. Hypertension in such cases is easily corrected with medications.

If slowly progressing nephritis occurs with urinary syndrome, then the clinical picture is also minimal, swelling is mild, and hypertension occurs in only half of the patients. A characteristic feature of this form is a noticeable change in the chemical composition of urine, which contains blood, protein, and sometimes leukocytes.

Classes of lupus nephritis

Clinical picture and symptoms of the disease

Lupus nephritis is characterized by general manifestations inherent in SLE and local ones that develop with kidney damage and are determined by the localization of the inflammatory focus.

General symptoms of the disease

Local symptoms

Depends on the morphological type of lupus nephritis. The following variants of the disease are distinguished:

It is divided into rapidly progressing and slowly progressing types.

Rapidly progressive nephritis is characterized by a severe course, extensive swelling of the entire body (nephrotic syndrome), proteinuria (protein in the urine), hematuria (blood in the urine), hypoproteinemia (low protein levels in the blood). Fluid often accumulates in the mediastinum and abdominal cavity.

Arterial hypertension in this type of disease is very difficult to treat. In 30% of cases, DIC syndrome develops, manifested by skin hemorrhages, uterine, intestinal, gastric, nosebleeds, anemia, and the formation of a large number of microthrombi.

Against the background of this form, renal failure may develop. Rapidly progressive nephritis is a life-threatening condition for the patient; the five-year survival rate is 29%.

The slowly progressive type occurs in 40% of patients with lupus nephritis and has a milder course. Nephrotic syndrome is mild, swelling is not so massive, and there is a moderate amount of protein in the blood and urine. Leukocytosis indicates the addition of a secondary infection. Hypertension is in most cases well controlled with medication. Ten-year survival rate without hypertension is 60-70%.

Inactive (latent) nephritis Characterized by moderate or mild proteinuria, hematuria, leukocytosis. Often there is no protein or blood in the urine at all. Kidney function is preserved or slightly reduced. Diffuse (focal) proliferative nephritis has a severe course, similar to the rapidly progressive type and has an unfavorable prognosis. Membranous nephritis is characterized by microhematuria, isolated proteinuria, and arterial hypertension. Mesahypoproliferative lupus GN Manifests itself as isolated urinary syndrome and nephrotic syndrome. Main symptoms: dizziness, nausea, loss of appetite, fluid accumulation in the peritoneum and mediastinum, proteinuria, anemia, lower back pain, shortness of breath, tachycardia. The urine becomes a dirty green-brown color. Mesangiocapillary lupus (lobular) GN A rare form characterized by urinary and nephrotic syndrome. Fibroplastic (sclerosing) lupus glomerulonephritis Manifests itself with increased blood pressure and reduced nitrogen excretory function of the kidneys.

Diagnostics

Diagnosing lupus nephritis is quite simple, especially in the presence of a typical clinical picture of the underlying systemic disease, coupled with specific signs such as erythema on the face, fever, arthritis, etc.

Laboratory diagnostic tests are required, including:

- Careful examination of urine for leukocyturia, hematuria, proteinuria;

- Blood tests revealing a deficiency of leukocytes, less often erythrocytes and platelets, an increased ESR;

The presence of autoantibodies and cells specific for systemic lupus are also detected.

Etiology of the disease

Lupus nephritis manifests itself as a result of increased insolation of solar radiation. That is why it is common on hot continents. Epidermal cells in the presence of a strong tan cannot cope with their protective function. As a result, complex inflammatory processes occur in the body.

In some cases, the appearance of lupus nephritis may be triggered by an allergic reaction to one of the components of the drug. Extremely rare, it appears as a result of a genetic mutation. Disturbed hormonal levels also negatively affect the course of the disease.

Treatment

If during lupus the pathological inflammatory process affects the kidney tissue and signs of lupus nephritis appear, then appropriate treatment must be started immediately. The main drugs used in the treatment of lupus are cytostatics and hormonal drugs, i.e. Cyclosporine and Dexamethasone. For lupus kidney damage, the following methods are recommended:

- Quit alcohol and smoking;

- Drink the right amount of fluid to maintain fluid balance;

- Do not eat foods containing cholesterol;

- Eat a minimum amount of food containing proteins, phosphorus and potassium;

- Move more, perform movements from the exercise therapy program;

- Monitor blood pressure, maintaining it at the required level with medications if necessary;

- Stop taking medications that negatively affect the condition of the kidneys (such as NSAIDs, etc.).

Often, treatment of lupus nephritis is based on the principles of pulse therapy - when the patient is administered loading doses of cytostatics and hormones throughout the day. After several weeks, pulse therapy must be repeated.

If lupus nephritis has led to an acute form of kidney failure, then the patient undergoes hemodialysis. For severe lesions, organ transplantation is indicated.

During remission periods, regular spa treatment is recommended. All patients, even after treatment, are under clinical supervision with systematic preventive examinations by specialists with a narrow specialization (urologists, etc.).

Preventive measures

The main point of preventing nephritis is timely treatment of an autoimmune systemic disease. Infectious diseases, as well as foci of chronic infection, must be eliminated in a timely manner. In addition, it is recommended to avoid hypothermia.

Daily meals should be fractional (at least 5 meals a day) and balanced. You should avoid eating fried and overly spicy foods and minimize the consumption of canned foods. It is useful to introduce fiber into your diet (found in greens, fresh fruits and vegetables).

It is necessary to stop smoking and drinking drinks containing alcohol.

Forecasts

The prognosis is determined by the correctness and timeliness of the selected therapy. In young patients, the pathology occurs in a more severe form. In addition, the duration of the period from the manifestation of systemic lupus to the onset of development of lupus kidney damage is important. The patient's gender also affects the prognosis, because women have a significantly higher survival rate. Although the pathology is serious, with timely and correct treatment, most patients with lupus nephritis live a completely normal life.

Classification of formations

The disease lupus nephritis occurs in several stages. Each of them has certain types of changes, which are accompanied by the following symptoms:

- Stage 1. Here, the glomeruli of the renal tissue membrane are presented in the form of a normal homogeneous structure;

- Stage 2. On examination, minor changes are noted in the mesangium area;

- Stage 3. There is glomerulonephritis, which affects most of the glomerular tissue;

- Stage 4. It is accompanied by the presence of diffuse glomerulonephritis;

- Stage 5. There is a pronounced degree of membrane glomerulonephritis;

- at stage 6, doctors note sclerosed glomerulonephritis of the kidney tissue.